Agile and Self-Organization in Real Life

How agility at work and home can help streamline life's complexities

At Palantir, we work in agile, self-organizing teams. The company also prioritizes work-life balance, something that’s desirable and very much welcomed for me. Everyone has their unique situations–mine includes raising two young children with my spouse.

During my time practicing agile, I’ve realized that being a parent is a great way to hone my agile mindset. In this article I’ll share a few examples of how I practice agility at home, which helps my family operate smoothly and gives me good practice and lessons learned to apply back to work.

Prioritization for maximum value given constraints.

On agile teams, I often take the role of a Product Owner–the individual who advocates for the client’s best interests by sequencing (and re-sequencing) work so that it delivers the most value to the client based on dependencies, resources, and user experience (UX) and technical constraints.

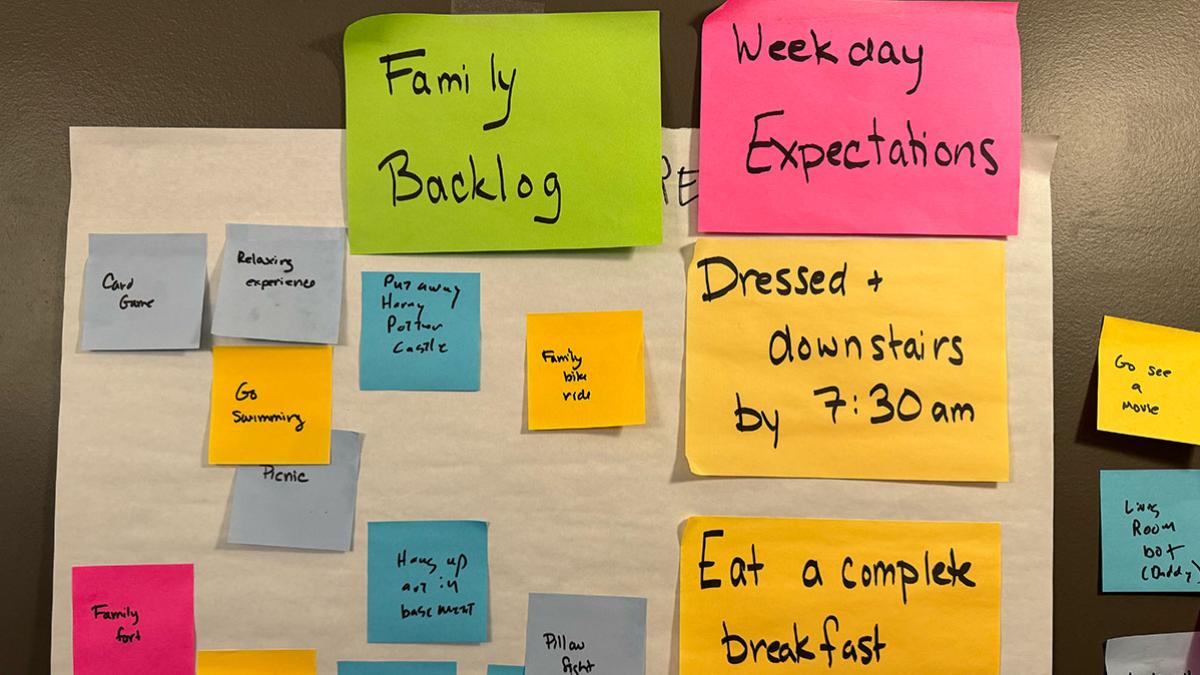

In practical terms, I take the list of things we and our client would like to have or do–our backlog–then prioritize the items on that list based on a lot of different inputs: what resources we have available, how much time we have, and ultimately what’s going to be most valuable.

Refining a backlog with a team means a lot of “ruthless prioritization.” And it does feel ruthless–it’s hard to say no (or not yet) to something people really want! But, doing this work helps the team clarify what’s important, urgent, and possible.

Anyone who’s had to get tiny humans out the door also knows the need for ruthless prioritization. You’ll likely need to deprioritize extra stories and playtime. What else might you take out of your morning routine for efficiency? Do you increase your timeline (like when I started waking up 15 minutes earlier)? Do you change the sequence–like getting dressed before breakfast? These are all worthwhile options, and ones that I experiment with and tune in our morning routine. These fairly low-stakes options with people I love build that muscle to help see the end goal of maximum value, which makes it easier to do at work.

Conduct safe experiments, and iterate.

An “experiment” in a self-organizing team is not scary–it’s a low-risk way to test a small, safe hypothesis and learn so that the organization can improve. Experiments are safe when they’re time-based, limited to a small scope, within given parameters, and conducted with team consent. An example of an experiment a project team might run is trying a new way of conducting an agile ceremony/event for collaboration and efficiency. For our family, fun and creativity are priorities, so we can experiment there.

We recently ran an experiment at my house, where my preschool-aged daughter wanted to play with real food (in particular, herbs and spices) in her play kitchen. We made this experiment safe to try by removing the cayenne and the glass jars, then reduced the set to some garlic powder and parsley.

The worst-case scenario in this experiment is that she’d make a big mess that we’d need to clean up. That’s exactly what happened! And we learned from the experiment. She loved it and played for a long time. Instead of shutting it down, we applied that learning to the experiment and gave her some carrots and potatoes. This iteration worked wonderfully with low cleanup. She had a positive, creative experience where she hosted a dinner party for her stuffies, and she ate carrots as well!

Times like these help me zero in on what is “safe to try” on project teams, knowing that experiments and iteration can lead to positive and sometimes unexpected results.

Advice and consent processes.

When you’re working on a self-organizing agile team, you need reliable methods to make good decisions when top-down isn’t an option. The advice and consent processes are two we use at Palantir; I’ve used it with success at home, too.

The advice process, for example, takes insights from multiple teammates while the decision is reserved for a single individual. At our house we have “Mom and Dad” decisions but we listen to our children’s thoughts, hopes, and concerns. An example is whether to use a vacation rental or a hotel for an upcoming trip. While the decision was reserved for us, we got insight from our children that vacation rentals often seem a little scary, and, well, there isn’t a pool. While the decision was reserved to us, taking in that information helped make a more well-rounded, thoughtful decision–and a process that I use often with my team.

Inspect and adapt – conduct retrospectives.

Finally we've adapted from agile to help us iterate to make things better incrementally. In a retro, we review what happened in our previous increment of work (sprint) and talk about what went well and what could be better. This helps us solve problems early on as a team.

We did some retros to examine why we were getting into a bad habit of being late to school. When cool heads were prevailing, we acknowledged that our routine wasn’t working. Rather than fixing the blame, we fixed the problem. My daughter and I brainstormed a bunch of ways we can make the morning go smoothly, then I narrowed it to three: we could wake up 15 minutes earlier, we could eat breakfast faster, or we could decide on lunch the night before. I asked her which one we should try the next day–a safe-to-try experiment! This kind of participatory problem-solving helps us keep our family tuned while maintaining our parental status as the decision-makers who keep things safe and smooth.

Agile in real life

Agile and self-organization are really practices for life, making complexity manageable. They’ve helped me prioritize to meet our family goals, find places to experiment and discover new ways to play and be, and find ways for us as a family to come together–within structure–to all participate in our decisions. It’s helped me make better decisions and find new opportunities at home, and it’s been good practice to bring back to work on my project teams.